The palimpsest of Ninfa

In the garden of Ninfa, an ambivalence is revealed through the protection, utilisation, conversion and restoration of historical structures and facilities. In Ninfa, the remains of a medieval village and its buildings were preserved and saved from complete destruction.

This approach would be impossible from today's point of view of monument protection because it does not take into account the authenticity of the place. The conversion into a garden was also carried out at the whim of a private developer. Historical relics were turned into romantic follies and staffages in an artistic garden ensemble. In order to be able to use them, they were altered and adapted to the needs of the users. The surroundings also have a direct influence on the garden when visual relationships with the surroundings change: because the previously agriculturally utilised mountain slopes now go fallow or when houses or power lines are built in the surrounding area that can be seen from the garden.

When conserving and restoring the garden, it is therefore always necessary to decide what condition can and should be restored. Today, the authenticity of the site is based on the fact that sometimes it was possible to go beyond mere conservation and make additions and changes.

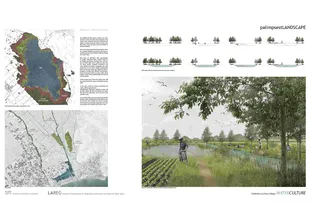

The Agro Pontino as a palimpsest

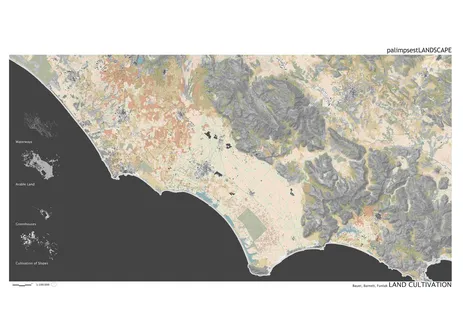

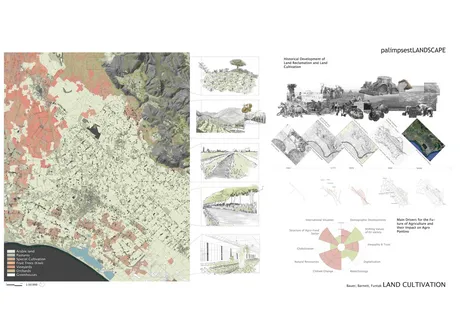

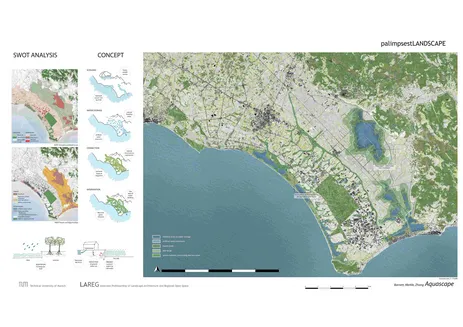

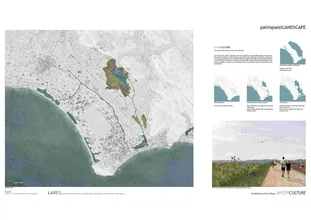

The landscape can be understood as a palimpsest in which inscriptions have been made, some have been erased and new ones have been added. The Agro Pontino contains historical structures that seem to have fallen out of time - such as ancient relics, settlement centres from the medieval period or of the 1930s. But which space has a greater claim to existence, which is worth protecting? Relics of the marshland, relics of early colonisation or relics of land cultivation? Should they be set free so that they can be viewed - or should they be usable in everyday life today? The Via Appia, for example, has been preserved in its spatial structure, while its materiality has been adapted to today's needs.

New inscriptions

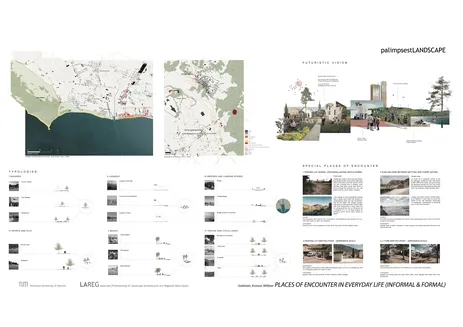

Questions that are posed on a small scale in the garden can also be asked about the landscape as a whole: Can the use of historical structures bring about change? How far-reaching a reorganisation may take place in order to adapt to current developments (adaptation) and anticipate foreseeable effects (mitigation)? What has cultural value in the landscape, what has intrinsic value as nature, what has everyday significance? Which structures should be preserved, restored or reconstructed and to what extent?

The challenges in the study project

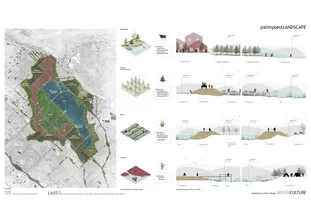

In the first part of the project, we look at the garden and the cultural landscape of Agro Pontino as a palimpsest. To do so, we separate the layers of time and meaning that have developed over the centuries, as a multi-layered work of maps, in order to gain a more free access to possible solutions for the above-mentioned issues arising from climate change and rural exodus.

New structures

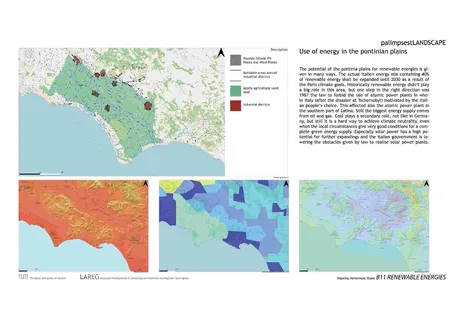

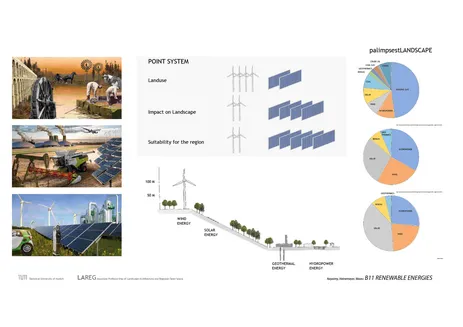

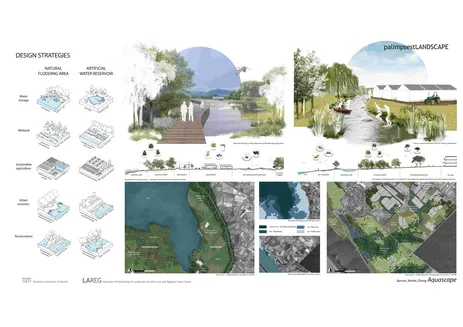

In the second part, new spatial structures are to be integrated into the existing palimpsest in the form of large-scale concepts that also enable new uses: the contextual integration of renewable energies, the questioning of previous land use and the handling of water as well as new forms of agriculture and housing.

All the different approaches are to be incorporated into a spatial design in the area around Cisterna di Latina, via Norma to Sermoneta, in order to bring together the possible solutions in a newly developed, consistent Mediterranean cultural landscape of the 21st century - with the garden at its centre.